Jefferson County, Alabama Breaks Free from 30-Year Consent Decree

With teamwork, vision, and sustained investment, Jefferson County, Alabama transforms its sewer system and marks a new era of stability and resilience.

Jefferson County’s Story

The devastating impact of unaddressed inflow-and-infiltration (I&I) on a utility’s sanitary sewer system can be difficult to measure. The tremendous burden on communities in terms of disruption, damage and dollars can be overwhelming and daunting.

Jefferson County was one of these communities — was. For nearly 30 years, the Jefferson County Environmental Services Department operated its 100-plus year old system under a consent decree, which stipulated specific upgrades and improvements to its treatment plants and entire sewer network. That is until September 2024, which marks the county’s officially release from the consent decree.

Pop the champagne corks, right?!

“Yes, it is nice to be a success story!” says Daniel White, deputy director of engineering and construction for Jefferson County’s sewer department. “This has been a total team effort over the years and there has been a lot of energy and effort to produce the results we have. We are committed to this view of sustainable and perpetual management of the sewer system. We don’t have a short-term view. We are always thinking long-term.”

A consent decree issued in 1996 forced Jefferson County to address the dire state of its sanitary sewer system, which was causing costly disruption of services and inconvenience for its community — and a lot of money. The county spent billions of dollars to achieve this massive, long-term turnaround.

Numerous trenchless methods were at the center of the work, most notably cured-in-place pipe (CIPP) for its mainlines and laterals, as well as manhole rehabilitation. Pipe bursting, microtunneling, auger boring and horizontal directional drilling have also played critical roles. Trenchless companies, such as BLD Services, Insituform Technologies, Puris Co., Duke’s, Infosense and SAK, and others all play key roles.

The system is operating at a level many communities across the country dream of having.

System Background

Considered one of the larger sanitary sewer systems in the country, the Jefferson County sanitary sewer system is a vast network that services more than Jefferson County and its primary city of Birmingham. The system encompasses more than 3,000 miles of gravity sewer lines. It includes 130 miles of force mains and more than 85,000 manholes. There are 177 pumping stations, and nine water treatment plants.

The system’s design is to treat 199 million gallons of sewage per day. It provides wastewater collection and treatment to more than 144,000 residential and commercial customers in the counties of Jefferson, Shelby and St. Clair, in addition to many surrounding cities.

The system itself dates back to the early 1900s, with heavy buildouts to handle the growing population and needs occurring throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. However, during that time and beyond, the patch work approach did not keep up with the volume and capacity issues, rendering the system basically non-functioning and creating higher costs, disruptions and headaches for the community.

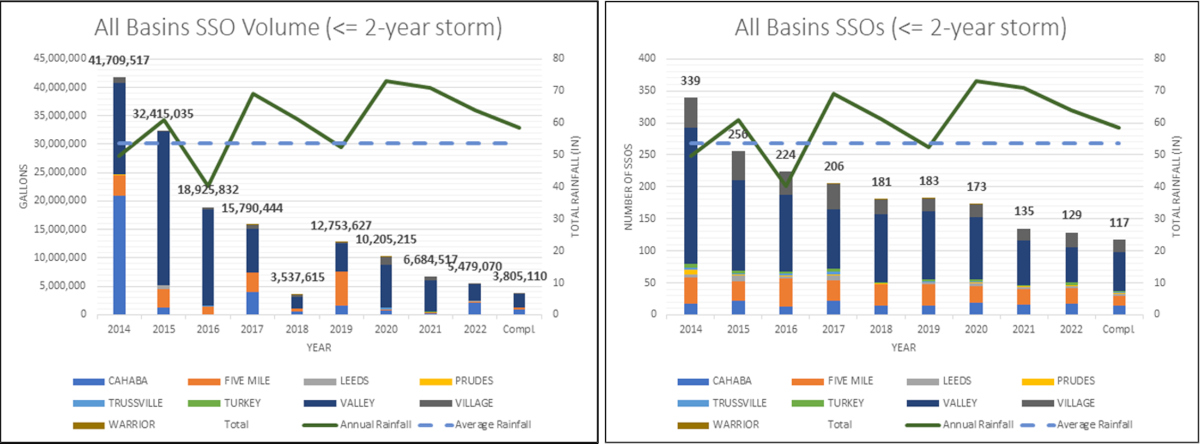

In simplest terms, the issues that led to the consent decree included automatic bypasses with the collection system and at certain treatment plants that discharge raw sewage into the surrounding creaks and streams, even under the most minor rain events. Additionally, sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs) routinely occurred throughout the whole network. The county neglected to properly maintain its treatment plants or reinvest adequately to handle normal, everyday flows, which led to high rates of violation.

The Consent Decree

After lawsuits were brought against the county due to the system’s condition, a consent decree was signed off in 1996 and the Jefferson County Commission went to work to meet the deadlines and projects/programs as directed. Between 1996 and 2006, the county spent $2.4 billion to meet the consent decree’s directives, which included major treatment plant upgrades and conveyance improvements. But the results of that work were less than ideal. Lackluster is a better way to describe them. Though Jefferson County met its obligations, the system still suffered from capacity issues, high SSOs and I&I numbers.

Why was that happening? Where was the huge reversal in issues?

“We spent $2.4 billion just to get up to a ‘poor’ operating condition rating. We started from a ‘dismal’ or ‘non-functional’ condition,” says White. “We spent $2.4 billion, and we looked like the other wastewater utilities of the day. We upgraded to the average.”

Consent decrees are strict, outlining specific steps recipients need to follow and milestones that must be met. Jefferson County had 203 action items that needed to be completed in the first 10 years. The end-result included more than 3 million ft of sewer lines rehabilitated using CIPP and roughly 20 percent of its gravity sewer system was renewed. Also, more than 400,000 ft of pipe was replaced. But it wasn’t enough.

I&I Continues

“We addressed structural deficiencies within the mainline sewer,” White says. “There was some hope that there was going to be this huge I&I reduction. And what we found was that there just wasn’t. The system continued to experience unusually high rates of I&I.

“We had 10 years to finish the first phase of the work. And, amazingly, we completed it on time,” he notes. “But because of that, it was one of the great failures. It was so rushed to get done on time, there wasn’t a lot of reassessments of strategy, adjustment to approach or measurement of results during the process. That time crunch was a real penalty and real negative for the results it produced.”

White and the Jefferson County Commission faced a significant workload, but they remained determined to push forward and elevate the system — on their terms. Although still operating under the consent decree, the county took control of the plans, programs, and timeline to ensure proper execution of the work.

In 2012, the engineering firm Hazen & Sawyer joined the team as program manager, coordinating, assessing, and prioritizing the sewer system overhaul. They tackled SSOs and I&I issues and developed a program to track progress and forecast future needs. Tad Powell took the construction management lead at the firm and has closely worked with White and the Jefferson County team throughout the process.

Program Stewards

White and Powell have been the long-term stewards of this program. White has served with the Jefferson County Environmental Services for more than 25 years, steering through the consent decree challenges from the very beginning. Prior to joining Hazen & Sawyer, Powell was a project manager for a trenchless rehab contractor. Both men are also Jefferson County residents, giving them more than just professional commitment — they shared a personal, vested interest to ensure their community had a top-rate sanitary sewer system for today and for generations to come.

“It’s not as easy as pushing play and going through the motions,” Powell says. “It’s personal to us. You see the results. We had chronic SSOs that would disrupt and debilitate people’s lives, for years. I’ve lived here and I’ve seen it.”

Jefferson County pivoted toward the next phase of the consent decree. Between 2008-2012, the county met its consent decree obligations with regards to five of its smaller basins. The team developed an assessment management program and implemented a results-based approach to address the system’s volume and I&I numbers. The target of all the work was the I&I.

Moving Forward

“I&I as the single biggest driver for the consent decree. It was I&I that was producing the bypasses, and producing the overflows. It was I&I that was contributing to some of the problems the treatment plants were experiencing because they were overloaded hydraulically,” White explains. “We are talking billions of gallons of untreated sewage per year. The impact was clear. The system did not meet the levels of expectation from customers, regulators and from the owner. It was a failed system and it was not working.”

The next 10 to 15 years, Jefferson County went to work in addressing this issue. This includes CIPP rehabilitation of more than 905,000 ft of mainline. The open-cut replacement of 250,000 ft of pipe, and some pipe bursting and tunneling. Once the county started seeing documented results, another aspect of its program came into play: preventative maintenance and rehabilitation.

Powell talks about the use of software programs and advanced technologies to assess and prioritize the needed work. Use of the SL-RAT from Infosense, for example, allowed crews to determine where defects and potential defects were.

“A byproduct of using the SL-RAT was that it was used at each manhole, upstream and downstream. Produced great data but it also required to have our guys walking and popping open manholes every day. They saw the physical condition of the manhole and could alert the sewer cleaning staff of any possible issues and possibly avert any SSOs,” he says.

End Results

Even though the court terminated the consent decree last September, White and Powell know there will always be work ahead. But having been through the grueling challenges of a consent decree, the county is working ahead — working proactively vs. reactively. And that is a gamechanger, they say.

“The first 10 years was very prescriptive,” White says. “We had a list of what to do and how to do it and the end-result was bad. We didn’t get the results we needed and the SSOs reductions that we hoped for. The last 10 years, we were given the autonomy to make our decisions. We had time plan, execute, assess and adjust. And that made a huge difference.”

“We’ve learned enough in this process to know that you cannot get behind,” Powell says. “It’s simple, but true. We understand [I&I] is a monster and we have to attack it every day. If we can get there early, that’s how we save money.”

White is more than proud about the accomplishments on his watch over the last 25 years.

“This is going to be the crowning achievement of my career,” White says. “It’s a single, definable event that looks at the culmination of the years and years of work that shows we achieved something that is lasting.”

Sharon M. Bueno is editor of Trenchless Technology.

Latest Posts

- NASSCO Report – The Key to Long-Lasting Sewer Structure Rehab: Think Holistically

- Jason Lueke Is the 2026 Trenchless Technology Person of the Year

- How to Extend Centrifugal Pump Life and Improve Operation

- NASTT Appoints Kim Hanson as New Executive Director

- How to Finance Your Growing Construction Company