Leaking Laterals Gaining Attention as System Owners Look to Combat I&I

The holistic approach to sewer rehab cannot be fully achieved without addressing the mainline-lateral interface, as well as the lateral pipes. The focus on sewer rehabilitation while centered upon mainline and manholes, recently has begun to shift its attention toward private laterals.

The question (or statement) that is always brought forward lingers around the ownership of the lateral pipes and the responsibilities of private vs. public funds to renew these systems. In many municipalities across North America, the majority length of the lateral pipe is within the rights of the private sector and therefore – in the system owner’s eyes – so lies the financial responsibility for the maintenance and upkeep of that system.

However, some proactive wastewater system owners have now taken the stance that although they do not own, they are affected by the inflow and infiltration (I&I) from private laterals and therefore have begun to approach the concept of lateral rehabilitation. Another approach includes appropriating funds for the sharing of costs to rehabilitate lateral pipes between public and private owners.

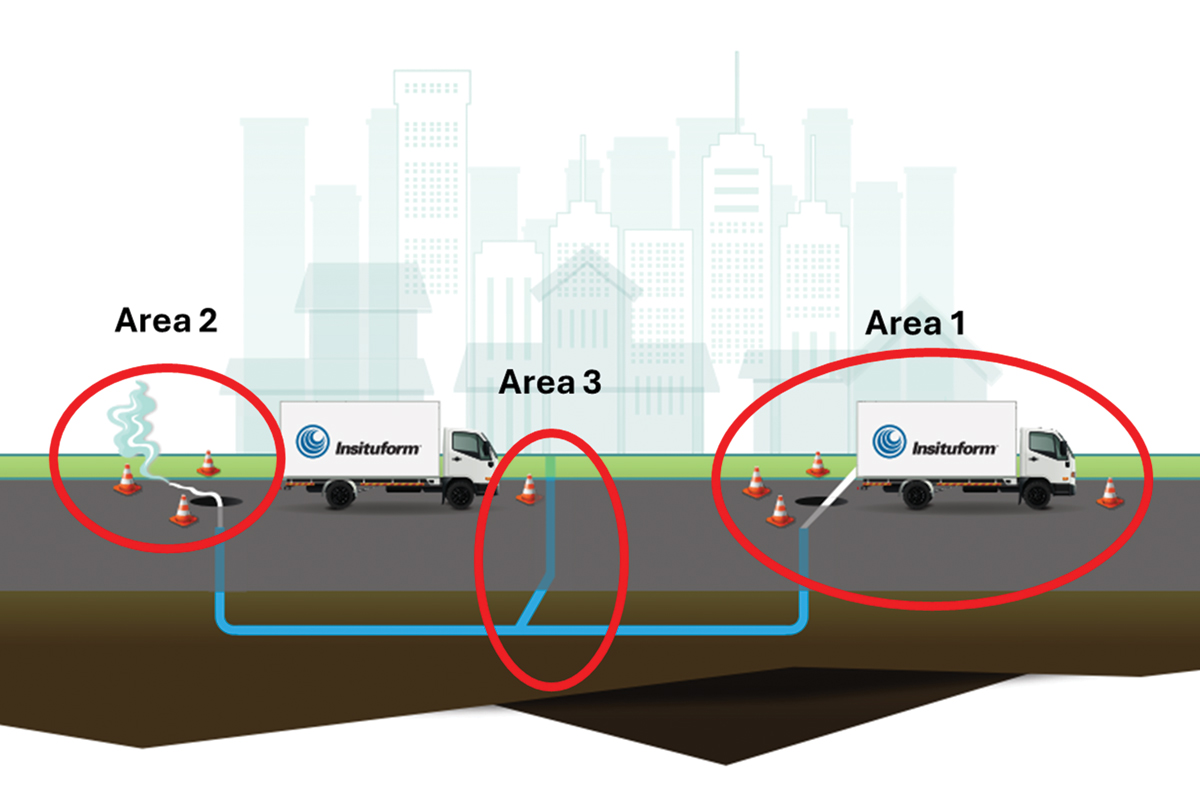

When a mainline system is renewed using mainline and manhole applications only, the groundwater that remains follows the path of least resistance along the pipe trenches and will find its next entry point at the laterals. In 1981, C.H. Steketee identified the issues with I&I mainline only programs and wrote: “The problems encountered are water-transmitting backfill materials, piping and erosion around the sewer pipes, stormed induced infiltration, difficulties in identifying the location of leaks in surcharging areas, transference of leaks to other location as holes are repaired, and the necessity to fix nearly all of the leaks in a section to make a significant improvement.”

I&I Reduction at the Lateral

Regardless of ownership or financial responsibility, unaddressed lateral pipes and interfaces affect a wastewater system by contributing a significant amount of I&I. This, in turn, greatly lowers the overall carrying capacity, creates the potential for sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs), and increases the amount of clean water that must be treated at wastewater plants.

Forward-thinking municipalities have already begun to address these areas within their collection systems as part of their rehabilitation and I&I reduction programs often as part of their lining programs. Municipalities are also beginning to revisit projects where lateral rehabilitation was not addressed during the lining phases. This is to complete the holistic approach by creating a “closed system” and further reducing the influence of I&I.

Verification of active pipes remains a top priority on the to-do list when beginning to address lateral rehabilitation. Often, the policy of many companies would be to reinstate every lateral connection after lining a pipe, as there were no items included in a project for inspection. This also eliminated the chances that an active service would be blocked or lined over on a CIPP project. By following this protocol, inactive lateral connections allow for open pipes within the pipe trench resulting in limited I&I reduction.

A simple method of verification would be to enter each private property and dye test the water outflow while observing with a camera inside the mainline. An easier, less obtrusive solution would be to launch a lateral inspection camera from the mainline while verifying above ground using a simple sonde and locating device. GIS readings of strategic pipe locations can also be included as part of the deliverables package which allows for the full incorporation of the data into local GIS databases. Inactive laterals found during these processes can be addressed using short liners with hydrophobic end seals, forgoing the reinstatement after lining, or filling the lateral completely with grout.

Structural and Non-Structural Rehab Solutions

Sealing a lateral using chemical grouting is a non-structural solution.

The process of installing grout is achieved using a lateral packer and sock system. The packer is inflated at the site of the lateral intersection and a sock is then inverted into the pipe. After both are fully inflated, a voided area is created between the unit and the pipe. Acrylamide grout is then pumped into the void through open joints where it gels, creating a seal on the outside of the pipe. In the case of cured-in-place pipe (CIPP), grout is also injected into the annular space between the liner and the host pipe.

Sealing lengths are dependent upon the overall length of the lateral plug. While it is common to use plugs that are 4 to 10 ft long, laterals have been sealed from the mainline using plugs up to 40 ft long. If a cleanout is available, sealing the entire lateral can be achieved using a push packer system that is inserted into the cleanout and then aligned with joints from the cleanout to the main and from the cleanout to the building.

Using CIPP technology, laterals are structurally rehabilitated using an installation technique from the mainline. Centered at the mainline, a full wrap liner is attached at the lateral liner sock and hydrophilic bands encompass the wrap at the three endpoints. The resin soaked felt liner is then inverted into the lateral and cured using steam, UV light or ambient heat. The hydrophilic bands swell when contacted by water, completing the seal.

If a cleanout is available, lining the lateral can be achieved through the inversion of the CIPP liner from the cleanout towards the mainline or back towards the home, addressing only the lateral pipe and not the mainline interface.

John Manijak is in business development at Hoerr Construction.