So Much More Than Mud

All that Total Boring gets from Bentonite Leader Wyo-Ben

Acquired in 2017 by brothers Dayton and Howard Betts, Total Boring Solutions LLC quickly established itself as reliable provider of high-quality, horizontal directional drilling (HDD) services. The entrepreneurs are the founders of two other successful companies, Betts Telecom (est. 1996) and 5GS (est. 1999). The addition of Total Boring allowed them to introduce driller Tanner Betts, Howard’s son, to executive management. Dayton now heads up Betts Telecom, Howard runs 5GS and Tanner manages Total Boring operations and business development.

In the five short years since Total Boring’s founding, Tanner Betts said, “It’s gone extremely well.” The company has grown exponentially but, Betts said, growth is not the priority. It’s simply a byproduct of reliable performance. His only vision is to be the best in the industry.

“Customers force you to grow. There is great customer demand for contractors who do what they say they’ll do. That’s why we keep growing. When a customer asks, ‘Can you do this?’ We always say yes. And we always do.”

Each year Total Boring’s productivity has topped the previous year. The pandemic shutdown did not affect infrastructure construction as much as it did many other industries. Total Boring’s business continuing growing throughout it. As for current market prices, “They’re not hurting us too much either so far. Maximizing footage, optimizing production, that helps take some of that pain out.” So far in 2022 they’re on pace to have their best year yet.

Choice of drilling machine, tooling, and “mud engineering” are key factors in optimization. Therefore, Total Boring’s fleet of drilling machines and tooling represent a varied mix of offerings of proven models from the market’s top-brand manufacturers. It needs just one vendor for its drilling fluid needs, however – Wyo-Ben.

Mud engineering

Always ready to share his insights with the industry about all aspects of drilling, Betts explained the value of the relationship. One is Wyo-Ben’s industry expertise in “mud” engineering – using additives to match drilling fluid characteristics to a given set of drilling conditions.

Wyo-Ben has been a global leader in both the production and innovative uses of bentonite clay since its founding in 1951. Today it operates three processing facilities in the Big Horn Basin region of Wyoming and Montana but is perhaps best known for its drilling fluid products, as well as drilling fluid education and training.

Bentonite clay itself has almost magical properties. The amount of bentonite mixed into water enhances its ability to efficiently evacuate chips from the hole, lubricate the tooling, and even maintain bore wall integrity in looser soils. Other additives can improve drilling fluid performance even further. Wyo-Ben offers a “mud school,” whose curriculum covers such things as clay chemistry, fluid dynamics and polymer usage.

Betts is himself a competent mud engineer, having spent many years as a machine operator. But drillers are notoriously production driven individuals. Having instant access to Wyo-Ben mud experts simply gives him additional resources to use as he optimizes drilling operations, especially for his larger and more complex jobs.

Wyo-Ben sales and training specialists Steve McGrew and Patrick McKelvey have been especially helpful to him, Betts said. McGrew recently conducted a Wyo-Ben mud school in the Total Boring conference room for Betts’ drillers.

Wyo-Ben also provides real-time, in-field support. “Steve can make all the difference on a job,” Betts said, quickly giving two examples to illustrate the point. One was a job in Texas, where “groundwater was mixing us up.” McGrew came to the site, showed the Total Boring team how to check their mud, and then stayed there with them to help monitor it.

The adjustment resulted in an immediate 15 percent increase in productivity. “Fifteen percent might not sound like much to someone outside the industry,” Betts said, “but consider that even a 5 percent gain is a significant value in a large-scale boring operation.”

Betts said McGrew’s input is a great value to him even when he’s already fairly sure his mix is dead on. If he can put an end to second-guessing, can stop going back to rethink his mix again, it gets him to his most productive setup that much faster.

“Drilling is a checklist,” Betts said. “You go through a list of items to overcome a problem or make sure you’re getting the best you can. You check your mud. You check your tooling, and so on.” When McGrew verifies his mix, Betts said, “Then I don’t waste another minute playing with it. I check it off my list and move on.”

On a Montana job drilling in cobble, Betts said, “The conditions were horrible. No one would expect to be doing well in that. But you still have to ask yourself, are you doing everything you need to do?”

Betts had made several adjustments to his mix before settling on what he thought was best. He made a quick call to McKelvey, just to check. “He agreed it was exactly what I should be running.” Confident the problem doesn’t involve his mix, he could turn his full attention to his reamers, switching first from “three-wings to PDCs and finally to rock tooth wagon wheels.” The wagon wheels did the trick.

Current job

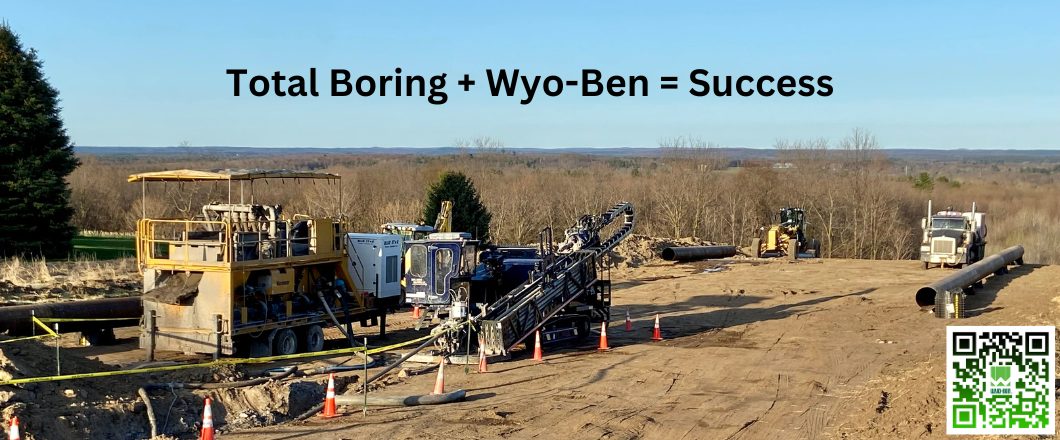

Total Boring’s job this day on an Upstate New York wind farm specified drilling 120 bores for 6- to 30-inch electrical conduit, all part of a high-voltage electricity collection system. Ground conditions were hard limestone and even harder pink granite with a compressive fracture strength around 20,000 psi or more.

Tooling consisted of PDC bits and Tungsten Carbide Insert (TCI) hole openers. Most of the conduit was poly pipe except for 30-inch steel conduit, which required 42-inch bores.

Typical length of a bore was 150 feet, with some longer. The longest was 1500 feet. Most called for a straight bore path. Some required a bit of radius.

Total Boring sent one of its dual-rod Vermeer D40✕55DR machines to start the job. “They’re good, reliable rock machines,” he said. Two Universal 120✕150 machines followed later on. “These Universals have good power for their class, which means more power from a smaller package.” In this application, he said, “They can be a more cost-effective alternative.” Plus, “They have good uptime and are easy for their drillers to maintain and service themselves in remote locations.”

Earlier in the day Betts had called McGrew to order three more truckloads of Wyo-Ben High Yield bentonite, which he uses for most of the jobs Total Boring typically takes on. He buys it from a local dealer when jobs are near enough to Total Boring’s Oklahoma headquarters. Elsewhere he orders it directly from Montana. “I have never once had a shipping issue,” he said. “Steve will give my order to Rita, who’ll have the shipping paperwork processed by noon. They’re punctual. If I say their driver needs to deliver by the end of a given 7-5 work shift, the driver’s there.”

On this job, the Total Boring crew is using a “seven-bag to 1000 gal. mix.” It has been working well for him, yielding production rates of about 150 feet a day in limestone and 75 a day in the pink granite.