Last Word – What Our Nation’s Drinking Water Systems Need Now

We must prioritize investments that make a meaningful impact on public health

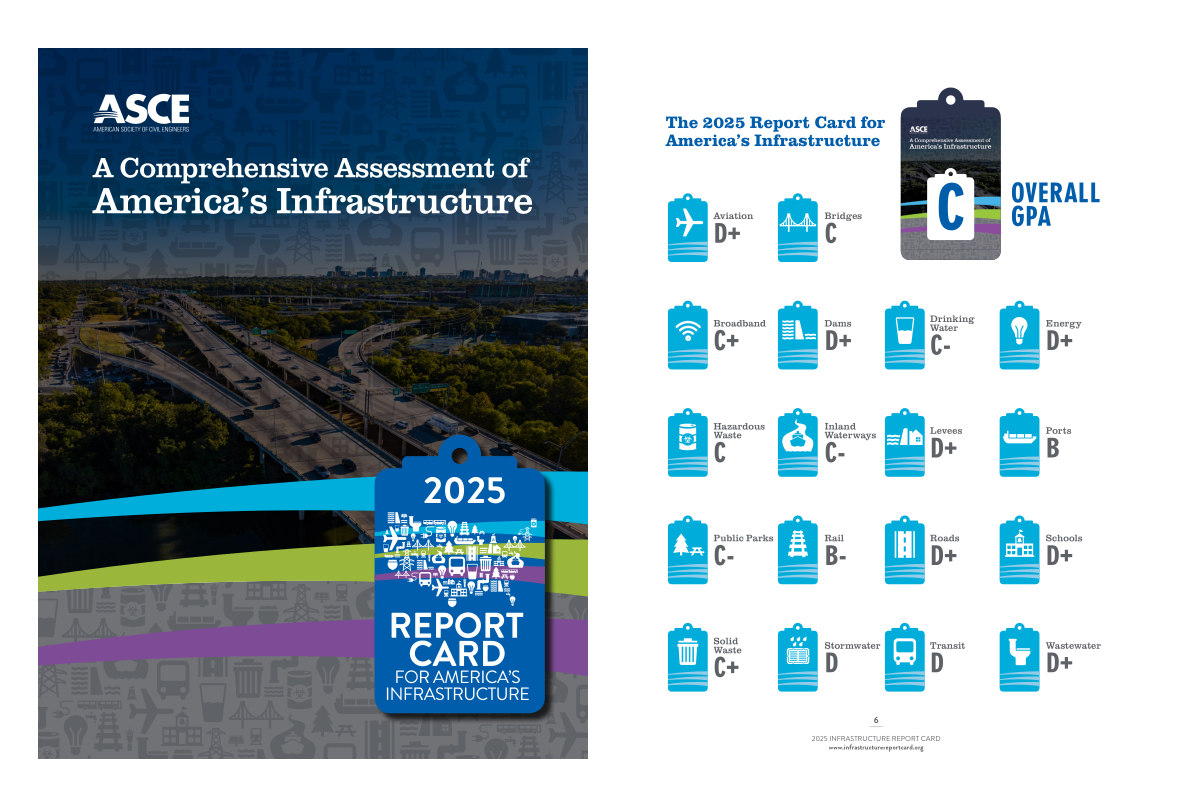

Our nation’s drinking water infrastructure is in desperate need of attention. Last year, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave our water system a C- and their economic study found that the annual drinking water and wastewater investment gap will eventually grow to $434 billion by 2029. The fact is that our nation’s drinking water infrastructure requires a massive investment.

President Joe Biden’s $1.2 trillion Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act includes $50 billion for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure improvements. This funding is significant, and the list of drinking water infrastructure needs is extensive.

RELATED: What’s on the Horizon for Lead Service Line Replacement?

Water systems need resources to hire and train personnel, maintain operations, replace and service aging pipes, and meet regulatory drinking water standards. With limited resources, there are important decisions to be made.

We must ensure government funds are distributed and spent on the most pressing issues that address the greatest public health risks. These taxpayer dollars must be carefully allocated using a science-based, risk- and cost-benefit analysis of drinking water issues. It’s not always beneficial to public health nor economically viable to address every potential or new water threat. Sometimes the greatest risk to water is the oldest issue, like aged drinking water pipes. It’s incumbent on our drinking water utilities and public health departments to prioritize the highest risk in public health threats. Applying a risk- and cost-benefit approach compares the range of pressing issues and helps determine the most beneficial public health investment.

Fortunately, this cost and risk-benefit analysis is woven into drinking water laws designed to protect our water supply. The Safe Drinking Water Act requires that regulations for our drinking water systems demonstrate a “meaningful opportunity for health risk reduction.” Since the Act was passed, proposed drinking water rules and regulations have been evaluated against this “meaningful” standard, and those that met it were set in motion.

RELATED: Last Word – Collaborating Toward the Next Dramatic Reduction in Underground Utility Damages

This same rigor to gauge public health impact must be applied to how these new infrastructure funds are spent. The agencies that oversee how these funds are spent must provide confidence that taxpayer dollars are protecting us from the risks that cause the greatest harm.

This analysis should not be time-consuming nor delay the urgency of the action required for drinking water issues. History sets the context for the present, and important insights can be taken from previous drinking water investments.

I had the good fortune to work with several water engineers and risk experts to create the Relative Health Indicator approach to help inform funding decisions by looking at the relative health benefits of addressing one drinking water contaminant over another. This approach quantifies potential health risk reductions by comparing the risk profile of a contaminant with other contaminants to create an objective and comparable scale of “meaningful opportunity” justifications.

The value of this risk-based approach is illustrated when considering the debate around perchlorate in drinking water. Many groups have advocated for more stringent regulations of perchlorate and costly measures to reduce levels in tap water. So, should regulators prioritize perchlorate over other pressing water infrastructure needs and would these costs meet the “meaningful risk reduction” standard? The Relative Health Indicator assessment shows that the risk of perchlorate falls below the lowest “meaningful risk reduction” threshold as defined by contaminants previously regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Drinking water risks are particularly high today for low-income and rural communities from contaminants that are already regulated yet not fully addressed. These communities are historically underserved and under-resourced.

Today, many lack the resources to properly address deteriorating drinking water infrastructure and exposure to the most dangerous contaminants. In some cases, they lack water infrastructure completely. These high-risk communities need to be at the top of our nation’s priority list. That’s why we urge regulators to continue to use this comparative risk analysis when investing in drinking water issues moving forward.