City of Portland, Oregon: Trenchless Programs Cut Costs, Provide Value to the Public

May 14, 2015

As one of the largest cities in the Northwestern United States, Portland, Ore., is known for many things that make it a culturally vibrant and livable city. If you’re into craft beer, then you may know the city contains one of the largest concentrations of microbreweries in the world.

As one of the largest cities in the Northwestern United States, Portland, Ore., is known for many things that make it a culturally vibrant and livable city. If you’re into craft beer, then you may know the city contains one of the largest concentrations of microbreweries in the world.Portland is also known for being green, and that’s not just referring to the landscape of the surrounding area. Magazines like Popular Science and Travel + Leisure have each ranked the city No. 1 of the greenest cities in America, and it can typically be found at or near the top of many other such lists due to its practices in renewable energy, recycling and LEED-certified building.

Undoubtedly, Portland’s environmentally-conscious mentality has also carried over to its underground infrastructure initiatives. So for now, let us focus more on the microtunneling than microbrews.

CSO Program & System Overview

Since completing its large CSO program in 2011, pipe bursting has been a big part of Portland BES’ trenchless programs to address aging sewer mains and laterals.

In 2011, Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) completed a 20-year program to update its sewer system and reduce combined sewer overflows (CSOs) into the Willamette River and Columbia Slough. The program was established in response to an order issued by the State of Oregon, which mandated the large CSO program.

The program included the construction of a series of tunnels using both microtunneling and conventional tunneling that tied into the combined sewers to collect overflows. Two of the major projects in the program — the West Side and East Side CSO tunnels — each were significant in project size and contracting strategies employed. The contracting strategies used to procure both the West Side and East Side CSO tunnels used a modified fixed-fee plus cost-reimbursable approach that allowed the contractor to have early involvement in the design process. The contracting model has since become known as “The Portland Method.”

Construction began on the first CSO projects in 1994, with the West Side CSO completing construction between 2002 and 2006, and the East Side CSO from 2006 to 2010. The East Side CSO tunnel was the largest of all Portland’s projects to reduce overflows to the Willamette River at 22 ft in diameter, six miles long and roughly 100 ft deep. The entire CSO program reduced overflows to the Columbia Slough by more than 99 percent and to the Willamette River by 94 percent.

Today, Portland’s combined sewer system provides sanitary and stormwater service to approximately one-third of the City’s area and the majority of its population, with a network of approximately 900 miles of pipes. The separated sanitary sewer system includes an additional network of 1,000 miles of sanitary pipes. Most combined sewers are concrete or vitrified clay and were built between 1910 and 1990. Pipe sizes range from as small as 6 in. in diameter to the larger collection tunnels at 22 ft. Based on recent inspection data, 70 percent of the combined sewer system pipes are now in good to very good condition, but approximately 10 percent of pipes are at high risk of failure and in need of repair or upgrading.

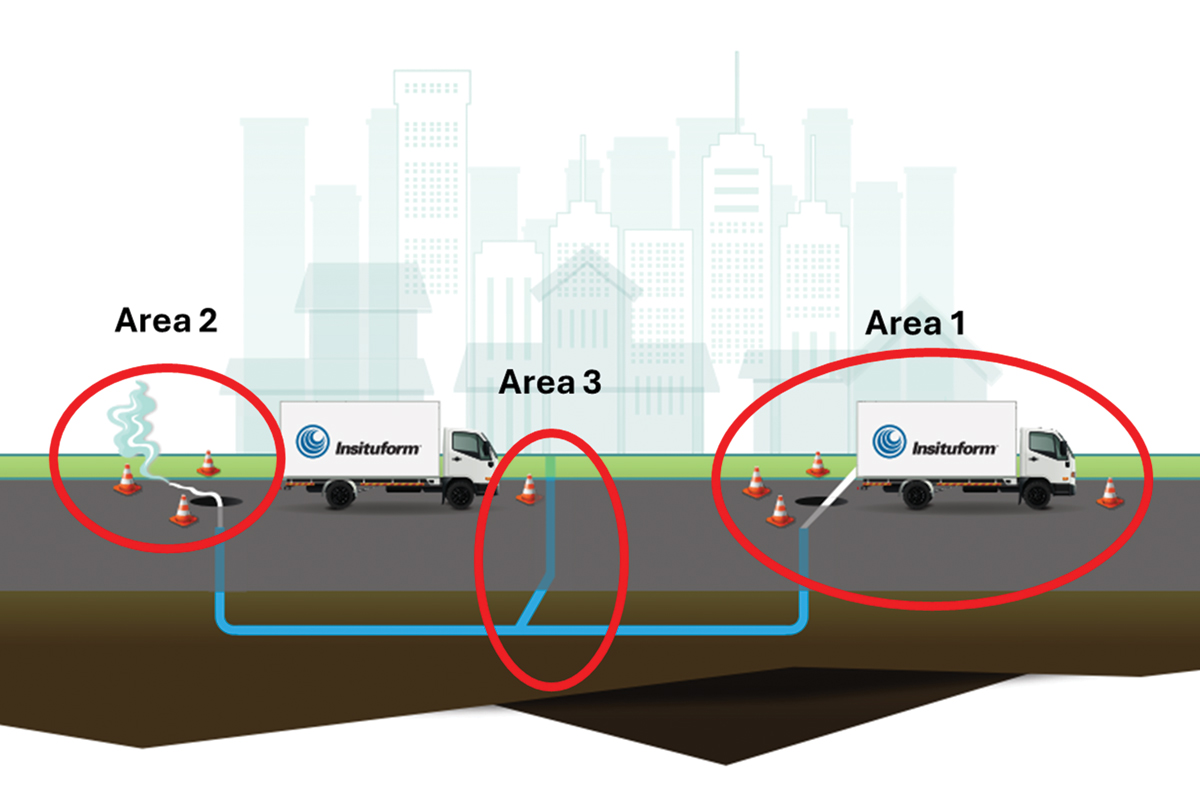

Since completing the CSO program in 2011, the BES has turned its attention to rehabilitation programs to address those sewer mains and laterals lines that are aging and in need of replacement. The approach is contrary to past practices in which many replacements were completed on a project-by-project basis to address pipes that had failed or were close to failing. The BES is currently involved in several projects that are bundled together into various programs using trenchless methods like CIPP, pipe bursting, jack and bore, HDD and pilot-tube microtunneling.

Mark Hutchinson, principal engineer and construction division manager for Portland BES, says the City has done cured-in-place pipe (CIPP) projects since about the mid-1980s and some pipe bursting projects over the last 20 or so years, but packaged trenchless programs is a new approach.

“During the CSO program, we did some trenchless work but we put a lot of time into rehabilitating the pipe system as a whole,” Hutchinson says. “Now we’re taking on these programs to address the worst of our worst pipes.”

Assessment

Toward the end of the CSO program, the BES began implementing asset management practices that included condition assessment of its sewer system using CCTV. The BES developed maps of the City — which it refers to as its “jelly bean” maps — that organize at-risk pipe sections in 10-ft segments and color coordinate them based on needed maintenance, cost-effectiveness and risk.

“Through CCTV on the sewers and rating them, we developed these big maps of the City and put together a computer model to assess the cost risk, the health risk and political risk,” says Hutchinson, who has worked for the City for more than 30 years. “We used to do individual pipe bursting projects and cured-in-place projects, so, for example, we’d do five blocks of this or 10 blocks of that.

“When we started the rehab program, we had all these projects and we didn’t know how to manage them and we noticed our costs were higher than other [cities]. So we started to package them based on geographic areas. Instead of putting out a $1 million to $2 million project, we tried to target a $5 million to $7 million project where we could get a trenchless contractor in for a year, develop the relationship, be able to work through the submittals and do some problem solving. We weren’t able to do that on three-month projects.”

Rehab & Replacement

By looking at the jelly bean maps, the BES organized rehab and replacement projects based on the high risk areas to be addressed in a series of trenchless programs organized by method — which includes an annual CIPP program — and other programs organized by geographic location. Hutchinson says the City initially began Phase 1, which included CIPP and pipe bursting projects to replace sewer mains, but soon realized costs were increasing and projects were slow due to difficulty in design.

“We projected the program at $250 million but we weren’t getting the projects out,” he says. “Instead of a project being a $5 million job, all of a sudden it was an $8 million or $10 million job. So we looked at some ways we could get ahead.

“We were using in-house design and also working with a couple consultants. They looked at this and suggested addressing some spot repairs rather than doing everything. So we started to let projects out in Phase 2 that had a combination of spot repairs, pipe burst and cured-in-place. Then we would line some of the laterals, some of them doing sliplining and some pipe busting.

“Some of these projects looked different from anything I’d seen in 30 years,” says Hutchinson. “But our contractors adapted and it really allowed us to get work done for closer to what our budget was and start to cover the risk.”

In-House

The BES’ collection system division oversees the operation and maintenance programs for the wastewater collection system as well as manages an interagency agreement for field maintenance services. City maintenance crews perform preventative maintenance CCTV, sewer cleaning, cut-and-cover sewer repair as well as CIPP repairs. In 1995, the City installed its first CIPP spot liner, a 30-ft long, 15-in. liner inside a commercial high-rise. Since then, the City has made significant advancements, installing sectional liners including a 120-ft segment of 10-in. liner, utilizing a robotic cutter of lateral connections and reducing costs by purchasing liner and resin in bulk. City maintenance crews completed lining of 8,000 lf of sewer mains last year in the 8- to 12-in. range and another 5,000 lf of lateral lining. What is unique is that they do not compete with the private contractors. The operations crew short sections up to 30 ft or laterals for emergencies or urgent situations, leaving the other pipe rehabilitation for the Portland contracting community to bid on.

Engineers in the maintenance engineering division also manage the design of emergency projects. Oftentimes sewer failures happen in challenging locations including under rail tracks, in the utility-congested central business district (CBD), or steep hills and are past the point of installing a spot liner. In these instances, the maintenance division will design a trenchless installation or rehabilitation and work with the construction management division to expedite the project.

In recent years, BES has also designed and contracted out over a dozen pilot bores including a pilot-tube microtunneling project adjacent to light rail tracks in the CBD under one of the oldest streets in the City. Other recent emergency projects include an auger bore under Union Pacific Railroad that included a 48-in. rehabilitation that involved jacking a 60-in. steel casing, pipe bursting a 22-in. sewer adjacent to light rail, and CIPP pipe in the CBD.

“The topography of Portland is particular a challenge on the west side of the City where we have some pretty significant slopes,” says Gary Irwin, wastewater collection systems manager who runs the operations and maintenance side of BES and oversees the maintenance services staff that focuses on emergency repairs.

“Steep slopes and forested areas contribute to some of the difficulties in trying to get pipelines repaired because pipes have been built over the years in all different locations — some accessible, some not. The Bureau is definitely not adverse to trenchless methods at all. It’s not always the right solution, but when we feel it is, there’s not a hesitation to employ a trenchless method.”

Challenges

Along with the cost-saving benefits that the bundled trenchless programs provide, limiting risk is another challenge and priority for the Portland BES. Hutchinson says implementing trenchless methods has helped in both areas, citing one example that stems from using trenchless vs. open-cut, which can result in damage to streets.

“One of our big risks in these projects is that our streets are as old as the sewers. If we’re not careful, we end up spending all of our money on the street rather than the pipe. We were seeing those costs in Phase 1, so we started shifting some of that cost to contractors.”

Hutchinson said on a couple occasions when a replacement project was bid with open cut, the contractors would come back and propose the same price but for pipe bursting. “So instead of seeing change orders in the magnitude of 10 percent for roads, we were able to do projects at the cost [originally proposed] and some things we were finishing under cost without having to worry about the roads,” he says.

Training Initiatives & Workforce

The City’s reinvestment in existing infrastructure and consistent trenchless projects has been a change of pace for Hutchinson, who was involved heavily in large tunneling projects during the city’s CSO program.

“I thought tunneling was the coolest thing in my career, but the fun thing now is to see all these different technologies,” he says. “I have 15 construction management teams so I have young people who are coming in and they’re taking these projects on and figuring out how to package them with the contractors. It’s been fun to watch.”

That’s another area of the BES that Hutchinson says he sees as proactive — training the workforce. According to Hutchinson, many of his longtime colleagues are retiring and much of the staff consists of employees with less than 10 years of experience. Hosting training initiatives and ‘lunch and learns’ with associations like the North American Society for Trenchless Technology (NASTT) along with vendors and contractors who come in to present case studies is one area the BES has been active in.

“We have roughly 100 people in our engineering group, and so it’s a way to take these people who are two, three, five years into their career and show them things. I could tell them but they’d probably say, ‘Yeah, that old guy doesn’t know what he’s talking about,’” Hutchinson jokes. “For me, that’s kind of the fun part of my career now is growing these other people who will carry it on.”

Trenchless Going Forward

With its large capital improvement program, Portland is active in repairing infrastructure and Hutchinson says bundling projects together is one way the BES has been able to make its funds go further while also limiting risk on projects. Another benefit in using trenchless, he adds, is working with a large program that provides the opportunity to do pilot projects to see what technologies and tools fit the program. Some of the projects currently in the pipeline for the BES include an I/I program that was recently started, several force main rehab projects, CIPP using UV curing and large diameter rehab that is part of the Phase 3 projects.

“We’re driven by the political risk,” Hutchinson says. “We have a City with light rail lines, old utilities and old streets and it’s a very political city so our commissioners don’t like to see problems for the public. So that drives some of our trenchless because we have no other choice. We can’t shut streets down, dig through fiber optics or 1900s water lines.

“The other part that drives [trenchless work] is cost. If we hadn’t been able to drop our cured-in-place cost by packaging, we wouldn’t be doing so much. I think we’re progressive. But there’s progressive because it’s cool and then there’s progressive because you’re getting the value for the public. I think we’re getting the value for the public.”

Andrew Farr is associate editor of Trenchless Technology.

Tags: May 2015 Print Issue